When In Doubt, Communicate!

By Richard Martin

The topic of my Monday Morning Brilliant Manoeuvres newsletter/blog about a week ago was communication within companies. You can read the posting here.

I wrote that executives and managers are much too secretive about their future intentions and plans, especially as concerns moving, closing, or opening facilities. They often keep their employees on pins and needles, not knowing about their immediate future, having to deal with the stress and uncertainty that arises as a result.

A long-time friend of mine who is an expert on communications strategy commented that there are a number of factors that must be taken into account before deciding exactly what to tell employees and the public about their intentions. I agree that there is a need for consideration and analysis, but in most cases, executives and managers are too secretive with their employees.

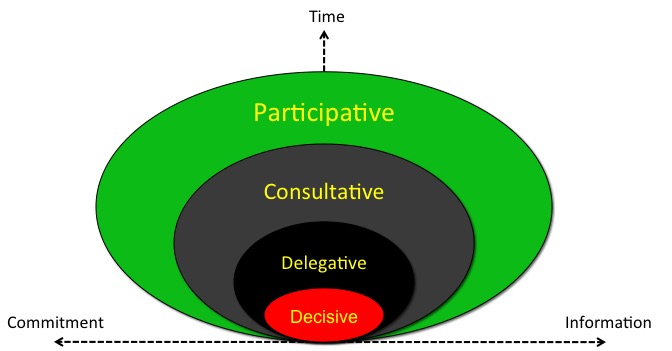

I’ve developed a model to guide leaders in delegation decisions, but it is just as useful in helping to determine how much information to give employees and followers about important decisions, and when.

There is a direct relationship between the three factors of Time, Commitment, and Information.

Time: How much is available; how important is speed to your decision; what is the degree of urgency/emergency; how complex is the task or project?

Commitment: How much employee/follower commitment is required; what is the task/project complexity; is there a major need to motivate and inspire employees/followers; are compulsion or obligation an option?

Information: Who has it; who needs it; is there a need to propagate and communicate it; can it be centralized or decentralized?

I wouldn’t call this a hard and fast rule, but in my experience, the three factors tend to co-vary. If you need a lot of commitment from your team, then, barring a genuine emergency, you have to give them the information to understand the situation and the time to analyze and digest its impact on them. Conversely, if you need information that only employees can provide, then you will require their commitment and have to devote time for integration.

These are just some of the questions your can ask before deciding how much to tell people about your intentions and plans. My default is always to say more than what habit or “normal” practice would indicate. What we often view as highly secret and confidential information is actually not that secret. To paraphrase journalist Gwynne Dyer (he was talking about military strategy): the big secret is that there are no secrets.

Yes, sometimes companies don’t want to spook suppliers and customers, and these are factors. But they aren’t the only ones. There is also employee morale and uncertainty to consider. For instance, if a company is considering moving a facility, employees might have to consider other employment opportunities that will be more convenient or less risky. No major urban center is without its traffic problems. Changing location can wreak havoc with employees’ ability and propensity to commute.

Moreover, as Aristotle said, “nature abhors a vacuum.” If there is no official information from reliable sources, i.e., managers and leaders, people will quite literally make it up. It’s a natural human proclivity. The rumour mill is harmful to morale and takes people away from their prime function, productive work. The further out the time horizon, the more the chances that rumours will be created to fill the information vacuum.

If you think you might be making a major change within, say, a year, then you can give a general briefing to your people. Tell them what your considering doing, why you’d be doing it, what factors you’re looking at, and ask them how this might impact them. Tell them you will keep them in the loop as much as possible.

You may actually get suggestions to improve your analysis and your resulting plans. It will also help generate commitment and engagement, and will quell rumours before they get out of hand. Morale will be less affected and you can look your employees in the eyes when you talk to them.

Back to newsletters